Shadowbanned: Art, Language, and Survival Under Digital Censorship

By Vianney Harelly

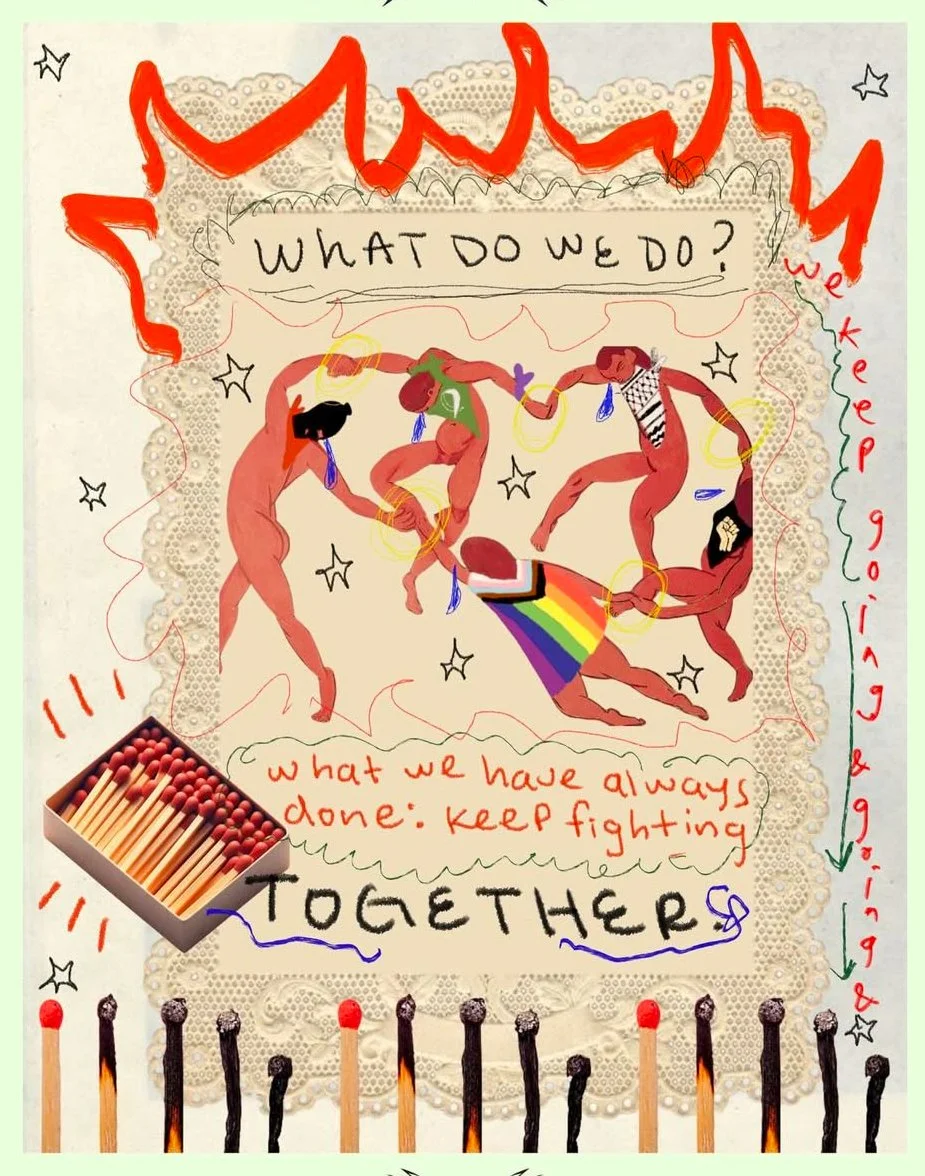

For the past two years, digital censorship has not been an abstract concept for me. It has been a material force shaping my life, my work, and my survival. As a fronterize, queer artist whose work holds personal history alongside political struggle, I have experienced firsthand how platforms label marginalized voices as risky, sensitive, or disposable. That censorship has come with a real cost.

Much of my work in support of marginalized communities has been flagged as “hate speech” or “violent,” resulting in extreme suppression and shadowbanning. My TikTok account is currently one strike away from being permanently taken down due to videos in support of Palestine and those speaking out against ICE. I rely on social media to share my art and sustain my small business. When my reach is cut, fewer people see my work, and fewer sales follow.

Over time, this has created profound financial strain. I have had to take on a second job, turn to crowdfunding, and live with daily chronic stress and anxiety. Each day feels like a battle to keep going, pushing forward with no guarantee that visibility or stability will return.

Language as Resistance

My work is shaped by language as resistance. I write in imperfect Spanglish and use non-binary, non-gendered language intentionally, refusing standardization as a form of compliance. This choice adds invisible labor to my process. Editing apps and captioning tools are built around standardized and gendered language, which means ensuring accessibility through captions takes me double the time.

Resistance also comes from audiences who insist on preserving “tradition” in language. English and Spanish are themselves colonial languages, violently imposed on Indigenous and native communities. Defending linguistic purity or perfection often reflects internalized colonization. Perfection, too, is a colonial demand.

Censorship Is Cultural Erasure

Censorship does not exist in isolation. It intersects with cultural erasure and digitalization, particularly for border communities, Indigenous peoples, and those across the Global South. Censorship is violence. Historically, it has been used as a weapon to silence marginalized communities. Artists of color often create work that reflects the truths of their time, and erasing that work is an attempt to erase those truths.

We know our history because our ancestors and martyrs were documented. Their testimonies survived despite relentless attempts to silence them. Power has always feared what it cannot control, and narrative is no exception. If art were not powerful, governments would not burn books or target journalists. This is why creating is not enough. We must also archive.

Borders and Platform Power

In late 2023, I dedicated my platform to Palestine solidarity and community organizing, recognizing that what has been done to Palestine has also been done, and will continue to be done, to my Mexican community. Since then, my engagement and financial stability have declined sharply. The strikes against my Palestinian content have placed my largest platform on the brink of permanent removal.

This reality exposes the myth of free speech. “Freedom” is selectively applied and exists only when it aligns with dominant agendas. Everything is political, including the apps on our phones. Silence is not neutral. Choosing not to speak is often exactly what the system requires.

Choosing Self-Publishing as Refusal

Because of this, I have chosen self-publishing and community-rooted creative work over traditional institutions. Studying English Creative Writing, I was confronted early with the question of which stories are deemed worthy of inclusion in literary canons. The answer was clear. Eurocentric, white narratives dominated.

Independent and self-published artists from marginalized communities are real artists. Self-publishing offers agency and creative freedom historically denied to artists of color. Women’s work has been erased under anonymity. Black authors have been forced to rely on white sponsors to be seen as legitimate. My dream is to create my own self-publishing house to archive and protect our testimonies.

Imagining true safety, autonomy, and cultural freedom feels difficult when survival consumes so much energy. Many days, I am focused simply on getting through. What I want is for artists who come from struggle, pain, rage, trauma, love, and hope to feel safe, visible, and supported.

I dream of a world where we are not forced to choose between speaking up and paying rent. I want our nervous systems to rest. While generational trauma is passed down, I believe peace and healing can be passed down too. Future artists deserve to know that a world exists where truth-telling is not punished.

I want us to create from passion, joy, and love, not from exhaustion and endurance. We have had to be strong for so long. It is time to simply be.

Vianney Harelly is a fronterize, queer artist, writer, and self-published author whose work explores border identity, language as resistance, and political struggle in the face of digital censorship. Follow her at @vianneyharelly.