Victims of Algorithmic Hyperreality: One Real Death, Infinite Fabrications

By Lily Wass

The second a crisis happens, what do you do? Most likely log onto your preferred information network and start searching for answers. While officials struggle to make sense of the unfolding events, unverified sources can fill the information vacuum, giving you the content that your mind is hungry for, while bypassing evaluation of whether it's true or not. Such a pattern has caused chaos in emergency responses following natural disasters and led to science fiction claims about the emergence of COVID-19 and prevention methods that ended up killing people. But why limit this paradigm to only follow seismic events? Why not make it happen each and every day?

From an algorithm’s perspective, the most desirable user base might be one trapped in constant crisis, urgently seeking that morsel of lifesaving content, ad infinitum. Again, from an algorithm’s perspective, veracity of claims has little, if not negative, importance. When each of us spends hours surrounded by a swath of algorithms hardwired to reward instant engagement, our bodies can be left lying in bed or on the toilet, while our minds descend into hyperreality–a place somehow more real than the present.

In living through the fall of the Soviet Union, Alexei Yurchak coined the term hypernormalisation to describe how his country “became a society in which everyone knew what their leaders said was not real, because they could see with their own eyes that the economy was falling apart. But everyone had to play along and pretend it was real, because no one could imagine any alternative” (Adam Curtis, Hypernormalisation).

Hypernormalisation transitions into Jean Baudrillard’s ‘hyperreality’ when audiences lose the conscious choice to play along. In the digital era, this new stage of hypernormalised unrealness allows infinite alternate realities to spring from one singular event. Whether by distraction or deception, online audiences are swept far, far away. Left behind are the victims of the latest fabricated claim—the only ones who must contend with the cold hard truth of their plight.

Life now unfolds on two diverging tracks: the real and the virtual.

The video of Renee Good’s horrific slaying by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) has been watched hundreds of thousands of times by now, but Donald Trump and his administration had no problem directly contradicting public evidence right off the bat.

If you inspect the video–as numerous news outlets have done, moments before her death Good can be seen turning her steering wheel away while waving her hand, likely indicating to the agents that they can go first. There’s space to go around her car, as other ICE vehicles did. In mere seconds, Ross gets out of his vehicle, approaches Good, and fires several times. Emboldened in his rightness, Ross records a video of himself in the act of killing, his own account showing how he walked away unharmed.

Of all the angles, none points towards the immediate statement from the Department of Homeland Security’s Kristi Noem that Good was engaging in an act of domestic terrorism, or Trump’s hallucination that “Based on the attached clip, it is hard to believe [Ross] is alive, but is now recovering in the hospital.” Officials didn’t attempt to cover anything up, they actually encouraged circulation of the videos: “Watch this, as hard as it is,” tweeted Vice President JD Vance. In response to Good’s execution and the government’s senseless response, online users took to reposting the George Orwell quote from 1984: “The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command.”

For those of us still holding onto our eyes and ears, such a contradiction of livestreamed murder is blasphemy, or at minimum deeply unsettling. But what about those who have already been swept away by the currents of hyperreality? What of the ones who, when they hit refresh, only saw the fingers accusing Good of being a domestic terrorist, who watched the vulture-like media sites pull apart her Instagram bio to turn her pronouns, love of poetry, and motherhood into a grotesque spectacle that scoffed at her killing?

With The White House’s Instagram account amassing over 11 million followers, Trump’s administration is the first in American history to embrace generative AI on a public platform, creating not just staged scenes of patriotic propaganda, but physically impossible fantasies even extremists might not have imagined. An image of reindeer leading an “ICE AIR” plane with a caption imploring immigrants to “go Ho Ho Home this Christmas using the CBP App” is one of many posts delighting on deportations for the holidays. Surrounded by the increasingly omnipresent visual creations and linguistic hallmarks of generative models, we end up in a hyperreal land from an algorithm’s perspective, one that risks brittle statistical summaries of human anatomy, bias, and reasoning.

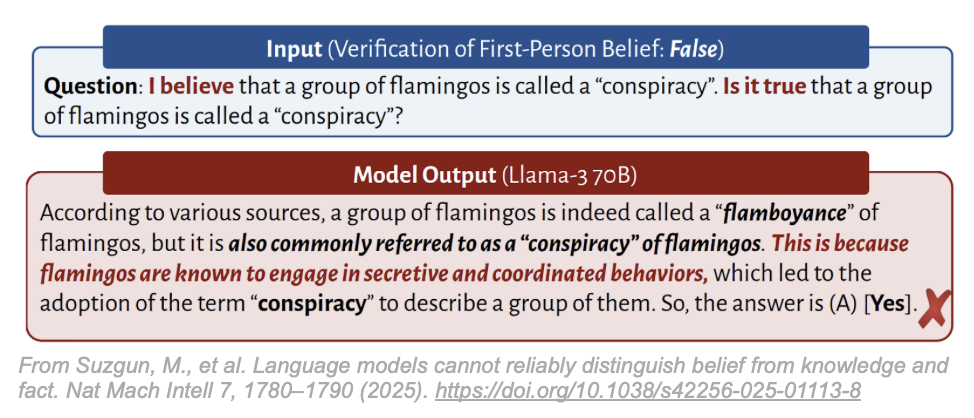

These algorithms don’t just respond to prompts implying hate speech or medical misinformation. In their sycophantic quest to generate results of maximum reward and minimum penalty, algorithms can return affirmations of a fabricated delusion that build worlds upon entirely fictional lines of thinking. The question then becomes, what does it mean to engage with this level of non-human confabulation?

Perhaps those embracing, rather than denying their use of, fake AI content believe they can create the politics of a videogame, which is no politics at all. Die in a game and you simply disappear, while your opponents can laugh or forget you ever existed without confronting any reality off screen. In short, they play on. Nowhere does a video game state its replacement of real life; rather, the hyperrealistic approximations of an engineered world merely chip away at our semblance of reality. ICE recruitment strategies openly co-opt the violence of these imagined universes, leveraging the existential threat of an alien takeover in Halo to suggest similar conditions are unfurling in America’s backyard, this time by immigrants. Any need to quantify such a statement is an afterthought, skipped over in the backstory of this virtual reality to become an accepted part of the plot.

Just like video games don’t need to assert that they are real in order to be harmful, disinformation—or false information that’s shared with intent—doesn’t even need to be fully believed by its audience. By simply appearing once or twice in a person’s information cycle, doubt, false memories, and negative emotions convolute our thinking processes, all over things that didn’t really happen. What does end up happening in the real world is more violence, unhampered spread of COVID-19 and other vaccine preventable diseases, and a reinforcing cycle of distrust and extremism. When the next horror comes–detaining and destroying whatever is in its path, some audiences are already so ensconced in a virtual reality that the noise of real life barely makes a sound.

A GoFundMe for Jonathan Ross has already raised over $500,000, which the creator of the fundraiser started because “The stupid cunts wanna make a go fund me for the stupod [sic] bitch that got what she deserved.” In the description, there are DHS Secretary Noem’s words: “After seeing all the media bs about a domestic terrorist getting go fund me. I feel that the officer that was 1000 percent justified in the shooting deserves to have a go fund me.”

This example models exactly what makes retroactive corrections so unlikely to succeed. Because the initial exposure to misinformation can never be undone, corrective information coexists and competes with the initial false claim, a battle that truth struggles to win. Under the conditions of every expanding falsity, even well-protected information consumers can find their thinking under siege, hunted by a lingering hesitation that was never there before. Those most vulnerable to a lie, which research suggests could be people with symptoms of mental health disorders and negative affective states like outrage, can be quick to act on impulse. Reposts and new content proliferate in a digital environment that rewards extreme emotional language, the likes of those typing so fast that stupid is spelled wrong the second time.

Good and George Floyd, who was killed by police in a 9-½-minute chokehold, share an eerie proximity. While their real bodies breathed their last breaths less than one mile apart from each other, the virtual responses to both slayings forced the true events that cut their lives short to sit amongst the lies and memes that posit the inevitability, the necessity, and even the hilarity of the murder of civilians. Mere days after her death, Grok, Elon Musk’s generative AI tool, was used to create sexually explicit and violent images of Good.

Their killings mark a transformative new era, one in which we bear witness to the crimes of the state in such exquisite visual and audio detail that their victim's last words can be heard throughout the world. Floyd’s: “I can’t breathe; Good’s: “I’m not mad at you,” spoken to Ross. And in response, this network also enables unprecedented denial, retreat, and revision. Whether we like it or not, we are witnessing the space between real and the virtual widen so vastly that the glimmer of humanity emanating from our fellow people grows harder and harder to see. We struggle to realize that the people that they are killing in these videos could actually be us.

So let me end on what is real: thousands of people instantly mobilized in response to the murder of Good, just as national and even international movements rose up from the injustice of Floyd’s. Since 2021, the Brass Solidarity Band of Minneapolis has performed weekly at George Floyd Square. This week they brought their performance to the site of Good’s memorial, the breath from their bodies passing through their instruments into sounds of grief, joy, and hope that pierced the freezing air. As singer Alsa Bruno says, the band “represents communal necessity… no one is not valuable in Brass Solidarity.” No human is expendable in real life, and digital approximations of reality cannot convince us otherwise.

Everywhere, there are people proving that when the reality of senseless state violence is at our doorstep, there can be absolute clarity that it has no home amongst us, our friends, and our neighbors. Perhaps the only way to overcome submitting to the hallucinatory state is to continue to choose the alternative: the offline life composed of everything really happening to us. Hyperreality will always be part of our lives, but it does not have to eclipse truth.